Dr. Margaret Cottle

I’ve written two articles now about the right to die and the right to live. The experiences I had taking care of my mother are what inspired me.

I’ve also touched on the controversy surrounding the Liverpool Care Pathway. It’s a care-withdrawal protocol used with terminally ill patients in the UK. At the moment, Canada’s Supreme Court is deciding whether doctors here should have the same rights.

Most of us aren’t against assisted suicide in cases where the person requesting it is of sound mind. In 1993, I remember sympathizing with Sue Rodriguez, a 42 year-old ALS sufferer from Victoria, British Columbia. She took her fight for the legal right to die to the Supreme Court of Canada. She lost twice and in 1994, took her own life with the help of an unnamed physician. I think she should have been allowed to fulfill her final wish, and to do so without endangering the freedom those helping her.

In 2012, Gloria Taylor, also diagnosed with ALS, was granted permission to end her own life. Taylor was granted an exemption to the law, but died of an infection before she could act on it.

Cases like Rodriguez’ and Taylor’s are compelling. They prompt us to question ourselves: what would we do if a disease like ALS found us?

Probably because of my relatively young age, I’ve always been on the liberal side of the assisted suicide issue. Thinking of Sue Rodriguez, I couldn’t imagine myself moving forward, calmly, into the future that awaited her. However, over the last four years, I’ve watched my mother adjust to a significant degree of paralysis and that has given me another perspective. We humans are a fairly adaptable bunch and, fearful though we might be, I suspect most of us are capable of adjusting to the worst.

For example, unlike Rodriguez or Taylor, my mother wanted to live, even with her poor prognosis. In part 1 of this series, “The Right to Die,” I detailed the difficult conversation I had with her, the  one where I told her what her future held. She was lucid and decisive. “I’m not ready to go” were her exact words; I repeated them verbatim when I asked to have her DNR reversed. The difficulty I had getting doctors to respect this reversal is outlined in Part 2, “The Right to Live.”

one where I told her what her future held. She was lucid and decisive. “I’m not ready to go” were her exact words; I repeated them verbatim when I asked to have her DNR reversed. The difficulty I had getting doctors to respect this reversal is outlined in Part 2, “The Right to Live.”

The Liverpool Care Pathway got my attention, probably because the controversy around it raises a lot of the same concerns I had when it came to watching the mishaps that befell my mother. She experienced a sequence of misdiagnoses, delays and postponements that were as inexplicable as they were catastrophic. I was dumbfounded by this: she had gangrene, a disease with an obvious symptom and an obvious cause. The death of one’s flesh is due to a loss of circulation; the only wildcard here is the question of what is causing it.

My mother

My mother was not treated in a timely way and what started as one serious problem – a gangrenous toe – compounded exponentially. She is now wheelchair-bound and paralyzed everywhere except for her right arm. I was left with the very clear impression she had not been taken seriously by the various doctors she consulted. My conclusion is based on three things: what she reported to me in our daily phone calls; the conversations I had with doctors I had asked to intervene; the stonewalling I encountered after the worst happened. No one was willing to explain exactly what had taken place.

The LCP is raising concerns, not because of its intent, which is to alleviate the suffering of the terminally ill, but because like most drastic solutions, it is not without its problems. Since I was the caregiver for an elderly parent, I’m going to start with what I think are the most obvious:

- Timing: As Dr. Patrick Pullicino states, in his critique of the LCP, “Predicting death in a time frame of three to four days, or even at any other specific time, is not possible scientifically.” It is also subjective. On the advice of doctors at my mother’s acute-care hospital, I signed a DNR for her in October, 2008. It is now December of 2012 and she is still alive. Another example: an elderly man Dr. Pullicino pulled off the LCP recovered enough so that he was able to return home. The 71 year-old had been admitted for pneumonia; another bout with it landed him in hospital 14 months later, at which time he was again put on the LCP. He was dead five hours later.

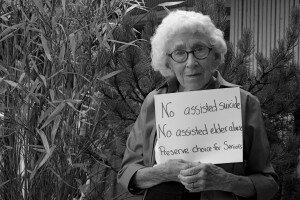

- Lack of consultation with families: Dr. Margaret Cottle, a palliative care doctor from BC, stated that in an article published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, a confidential study showed that a full 32% of 208 Belgian doctors had performed assisted suicide without the knowledge or consent of the families of patients. A further 20% had euthanized patients without the patient’s consent. They felt that to have that conversation – like the conversation I had with my mother – would stress the terminal patients too much. It was simpler, instead, to euthanize. The same lack of consultation is a problem in the UK. It was the families of patients, for example, who raised the initial alarm about LCP; they did so when they realized loved ones had been put on the pathway, also without their consent.

-

Creating the conditions and premature deployment: In part 1 of this series, I wrote about Diana Ford’s struggle to keep her father alive. Like Rodriguez, she is also taking her case to court, via the Ontario Appeals Board. Her argument? Many doctors habitually under-treat the elderly, allowing dangerous conditions and diseases to worsen. By doing so, they are creating favourable conditions for a protocol like the LCP. In my mother’s case, her symptoms of diminishing circulation, and then her gangrene, were treated as if she were on a slow boat to China. Although gangrene is potentially fatal, there was no urgency in her treatment that I could detect. As Patrick Pullicino has noted: “Very likely many elderly patients who could live substantially longer are being killed by the LCP.” Why? Because it’s the elderly that are particularly susceptible to the deployment of these

My mother and her loving caregivers, Vivian, Shannon and Lucy

passive, let-nature-take-its-course strategies. It’s hard to imagine a doctor allowing a 32 year-old, with symptoms similar to my mother’s, being treated in quite the same way.

- The use of funding to promote the LCP: In England, reporters using the Freedom of Information Act discovered that hospitals that met quotas for putting patients on the LCP received significant financial rewards. Hospitals that failed to meet those quotas were heavily penalized. (One source of one hospital’s funding was halved when they didn’t hit their “target” numbers.) This creates a top-down incentive: administrators are motivated to look the other way when the LCP is abused. They do so to maintain high funding levels and to keep their jobs.

- Incapacitated patients may be abused: Not all sons and daughters are capable of taking care of their parents. Not all relatives or people who have power-of-attorney are honest. They may support the hastened death of an elderly relative or ward because they stand to gain financially. Again, this is a particular risk for older patients: most younger patients haven’t had the chance to accumulate wealth and most of them, like Sue Rodriguez for example, are of sound mind. The elderly are more likely to have significant assets and are also more likely to suffer from conditions which interfere with their decision-making. Easy access to the LCP may aid unscrupulous legatees.

These issues are not reasons to withhold a treatment like the LCP from everyone. For patients who are discernibly close to death, and who are in extraordinary pain, the LCP is humane if it is what they choose. The problem, of course, is creating a decision-making protocol to protect those most vulnerable to its abuses. The elderly are far more likely to be hastened towards death, as their deaths seem imminent and inevitable anyway.

In conclusion, we need to hold families and doctors accountable when the decision is made to end a life. Mandates for care have to be explicit and difficult conversations have to happen. The LCP pocket guide, the link to which I am providing below, is shamefully vague. As someone who teaches young people, and insists they express themselves clearly, I read this pamphlet with dismay: it is one of the worst examples of weasel-wording I’ve ever seen.

http://www.liv.ac.uk/media/livacuk/mcpcil/migrated-files/liverpool-care-pathway/updatedlcppdfs/LCP_Pocket_Guide_-_April_2010.pdf

The LCP protocol entails the withdrawal of food, water and medication. Patients are sedated so that they don’t feel these deprivations and their suffering is minimized. Nowhere in this pamphlet are those hard facts made clear. They should be: the terminally ill and their families deserve to know the truth.

I hope the Supreme Court of Canada chooses well. The law may need to change, but piss-poor ideas about transparency have to change too. Just making it easier for doctors to euthanize patients is not the answer.

Part 1, The Right to Die: http://ireneogrizek.ca/2012/12/26/the-right-to-die/

Part 2, The Right to Live: http://ireneogrizek.ca/2012/12/27/5638-the-right-to-live/

Never heard of this “protocol” before reading your posts. Sounds like 1984. I am a senior and all alone, and my Mom left me antiques and her collections of a lifetime. I fear going in hospital now so the “vultures” can sieze our lifetime property. I would rather take our possessions out into a field and smash them all up rather than let a bunch of pigs benefit from our collections. My Mom, by the way, was murdered in hospital by the greedy American insurance industry before she could sue them after falling at a motel in Nebraska. At 92 she suffered a broken hip; I was too far away to catch her on crumbling curbing. Thank you for the insight, R Palmer

I have just written a hugh speil and lost it!!! So I will just

> say that my sister was inappropriately and illegally put on the LCP.

> We have had to deal with so many lies and cover ups and From Drs

> nurses and senior hosp. staff !! Unbelieviable! It is currently being

> investigated by the Health Ombudsman who appear to be taking it

> seriously. If you wish to know more I will supply. I am up for any

> campaigns to publicise the inappropriete use of the LCP.and starting

> with the govt who are giving Drs the power to decide who should live

> and who should die. i fail to see the difference between The LCP and

> murder. The motive is to reduce costs and make more hosp beds

> available, and the intention is very clear to take someones life. End

> of life care has always been available for terminally ill patients

> what appears to have happened now is that it is used for the old and

> infirm as a self- fulfilling prophesy and the option of “CARE” is not

> available.And true –many relatives do not want the responsibility of

caring for their very ill,demanding or otherwaise frail old people.

> Incidentally the Mental Capacity Act (on internet)is a very useful

> document.

I find it sad that the LCP is being compared to murder when it is a pathway which was born out of humanity and love. Eileen, I am so sad to hear that you have had such an awful experience, but I have to say that where I work nothing is done without thorough discussion with the patient, if they are able, and their family. If the family wishes for medication and nutrition to continue we will do so, even though it means inserting an NG tube.

There is no fine line between a good and a bad death, yet so many still die badly. The LCP was designed to ensure no one suffered at the point of death, and used correctly it works well. My patients are reviewed every four hours by nursing staff to ensure they are receiving appropriate care and every death is a sad, sad time on my ward.

I found your blog from the link you posted on the Scotsman article (re Lothian hospitals and the LCP). Thank-you for posting the link, thank-you for your blog.

I was a volunteer hospice chaplain in the US for years before going to live permanently in Scotland. In all the years I was a part of hospice care for the dying I never saw an IV drip pulled as part of a ‘humane and compassionate’ end to life-NEVER. Yet it is done here in the UK routinely as a feature to the LCP and patients die from dehydration-not the condition that saw them in hospital.

I personally believe the sedation is NOT for the patient’s comfort as they die from starvation and dehydration but is used to keep them still and quiet so as to avoid demonstrating their agony. The family thinks their loved one is going quietly, and the nursing staff don’t have to cope with the ‘disturbance’ on the ward or filtering out of what ever corner they’ve shuffled the victim off to.

I’m sorry, Julia Litt, but the LCP is murder and I cannot wrap my mind around the thought that any health care professional who would defend it. The only thing I can think is that your particular trust doesn’t pull the drip and so you have never seen the horror these patients go through.